SERIOUS PATHOLOGY(Pangarkar, Sanjog S et al., Bardin, Lynn D et al.)

| Possible serious conditions | Red flags (signs, symptoms, and history) |

|---|

| Cauda equina syndrome or conus medullaris syndrome | - Urinary retention

- Urinary or faecal incontinence

- Saddle anesthesia

- Changes in rectal tone

- Severe/progressive lower extremity neurologic deficits

|

| Infection | - Fever

- Immunosuppression

- IV drug use

- Recent infection, indwelling catheters (e.g., central line, Foley)

|

| Fracture | - History of osteoporosis

- Chronic use of corticosteroids

- Older age (≥75 years old)

- Recent trauma

- Younger patients at risk for stress fractures (e.g., overuse)

|

| Cancer | - History of cancer with new onset of LBP

- Unexplained weight loss

- Failure of LBP to improve after 1 month

- Age >50 years

- Multiple risk factors present

|

| Axial spondyloarthritis | - Morning stiffness that improves with exercise

- Alternating buttock pain

- Younger age (20–40 years)

- Positive family history of spondyloarthritis

- Extra-articular manifestation

|

SPECIFIC PATHOLOGY (Pangarkar, Sanjog S et al.)( Bardin, Lynn D et al.)

| Possible Other Conditions | Red flags (signs, symptoms, and history) |

|---|

| Herniated disc | - Radicular back pain (e.g., sciatica)

- Lower extremity dysesthesia and/or paresthesia

- Severe/progressive lower extremity neurologic deficits

- Symptoms present >1 month

|

| Spinal stenosis | - Radicular back pain (e.g., sciatica)

- Lower extremity dysesthesia and/or paresthesia, Neurogenic claudication

- Older age

- Bilateral leg pain exacerbated by extended posture

- Severe/progressive lower extremity neurologic deficits. Symptoms present for >1 month

|

| Inflammatory LBP | - Morning stiffness

- Improvement with exercise

- Alternating buttock pain

- Awakening due to LBP during the second part of the night (early morning awakening)

- Younger age

|

| Radicular pain / radiculopathy | - Leg pain is typically worse than back pain.

- Leg pain quality — sharp, lancinating, or deep ache increasing with cough, sneeze, or strain

- Leg pain location — unilateral, dermatomal concentration (below the knee for L4, L5, S1)

- Numbness or paraesthesia (typically in the distal dermatome)

- Weakness or loss of function (e.g., foot drop)

|

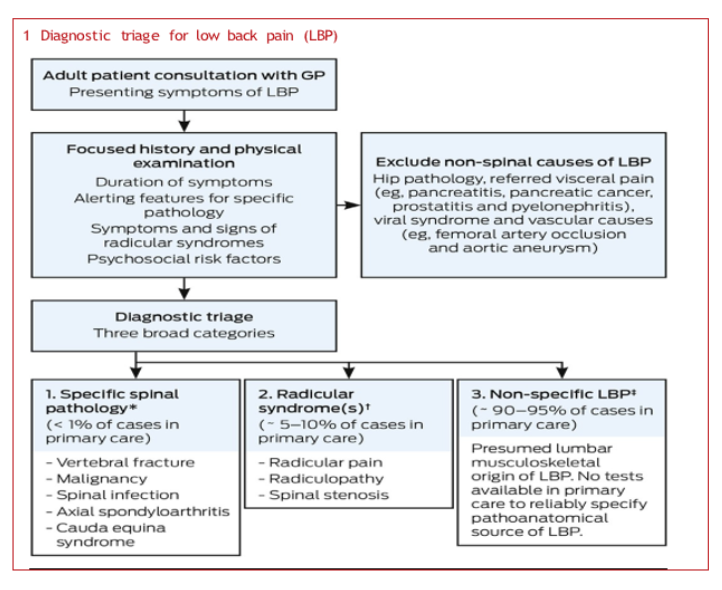

NON-SPECIFIC BACK PAIN

Do we need imaging for back pain?

For patients with acute low back pain, without focal neurologic deficits or other red flags (e.g., signs, symptoms, history), we recommend against routinely obtaining imaging studies or performing invasive diagnostic tests. [Pangarkar, Sanjog S et al.]. Because structural damage can be present in asymptomatic individuals.

Pain ≠ Damage. Age-specific prevalence estimates of degenerative spine imaging findings in asymptomatic patients. [Brinjikji, W et al.]

| Imaging Finding | 20 yr | 30 yr | 40 yr | 50 yr | 60 yr | 70 yr | 80 yr |

|---|

| Disk degeneration | 37% | 52% | 68% | 80% | 88% | 93% | 96% |

| Disk signal loss | 17% | 33% | 54% | 73% | 86% | 94% | 97% |

| Disk height loss | 24% | 34% | 45% | 56% | 67% | 76% | 84% |

| Disk bulge | 30% | 40% | 50% | 60% | 69% | 77% | 84% |

| Disk protrusion | 29% | 31% | 33% | 36% | 38% | 40% | 43% |

| Annular fissure | 19% | 20% | 22% | 23% | 25% | 27% | 29% |

| Facet degeneration | 4% | 9% | 18% | 32% | 50% | 69% | 83% |

| Spondylolisthesis | 3% | 5% | 8% | 14% | 23% | 35% | 50% |

Don’t rush for treatment!

Similarly, the medicines we call “painkillers” are not very effective at treating low back pain and often come with significant side effects.

They do not speed up your recovery and have greater potential for harm. For patients with chronic low back pain, we suggest against opioids.[ Pangarkar, Sanjog S et al. ]

Core stability: A myth?

There are a lot of things that can impact and influence someone’s LBP, including but definitely not limited to core weakness. When relevant, we should address deficits in not just the strength of the glutes and core, but mobility and stability of surrounding structures that may be impacting the load demand at the low back.

It may sound simple, but education and encouraging movement are one of the best, most researched methods of improving persistent pain. LBP is no different.

Build strength (not just in the core). [Reyes-Ferrada, Waleska et al]

Mind Your Back: Mind Your Language!

“Sit Up Straight.” In the absence of any good evidence that one posture exists to prevent pain, asking patients to work hard to achieve correct posture may set them up for a sense of failure and create more anxiety when their pain persists.

There is no single “correct” posture. Despite common posture beliefs, there is no strong evidence that one optimal posture exists or that avoiding the so-called “incorrect” postures will prevent back pain.[ Chun, Se-Woong et al.] [Laird, Robert A et al.]

Don’t be fooled by quick fixes!

1) Healing through needles

Acupuncture may not be a miracle cure, but it’s definitely an experience worth trying—especially if you’re into holistic healing, gentle approaches, or just want an excuse to lie down for 30 minutes without your phone.

For patients with chronic low back pain, we suggest against acupuncture. Acupuncture appears to have a small benefit for the reduction of pain for those with chronic LBP in the intermediate-term (3 – 12 months). [Pangarkar, Sanjog S et al.]

Thirty minutes later, I was “reset,” “aligned,” and stood up. But my back still hurts, and now it hurts with intention.

Based on the available evidence, there is moderate evidence showing no statistically significant differences in short- or long-term outcomes between traction as a single treatment and a placebo, sham, or no treatment. [Delitto, Anthony et al]

3) How to “Realign” Your Spine With Cracks

Step 1: Believe in the Myth.

Forget muscles, discs, nerves, biomechanics, and neuroscience. The only thing standing between you and a pain-free back is a good crunch sound effect.

Step 2: Chase the Pop.

Remember: relief isn’t measured in actual stability, mobility, or healing… It’s measured in decibels. Louder = healthier. POP = PROGRESS. Ignore biology.

So after all the hype about “targeting the exact misaligned vertebra”, high-quality evidence says: “Yeah… just pick a spot and crack it, you’ll get the same result.”

Precision? Not so much. The spine doesn’t seem to care which bone you pretend to realign. [Nim, Casper et al.]

Which suggests the effect isn’t from “rearranging the spine” — it’s likely non-specific factors (placebo, patient expectations, therapist interaction, natural recovery).

“Back Pain and Rest: Helpful or Harmful?”

Instead of prolonged rest, current guidelines encourage staying active with tailored movement strategies that support recovery. Graded activity focuses on gradually increasing physical function based on what the person can tolerate, helping reduce fear of movement and improve long-term outcomes. [Maher, Christopher G et al.]

So what works for low-back pain?

In a world full of medical jargon and worst-case scenarios seen on the internet, simple, compassionate reassurance with movement is often the most powerful medicine.

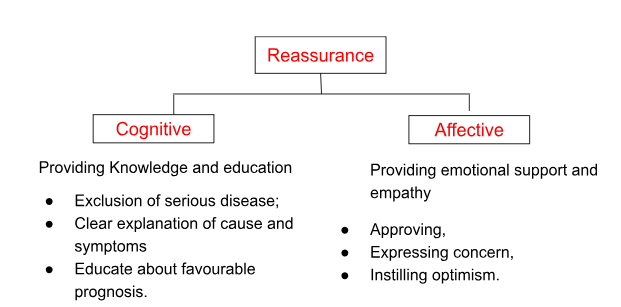

So, how to reassure [Pincus et al, 2013]?

Reassurance can be cognitive and affective.