Shoulder pain is one of the most common musculoskeletal conditions, and for years, the term “impingement” was used to describe pain caused by the rotator cuff tendons being compressed under the acromion and humeral head during arm elevation.

However, new evidence shows this idea is outdated, leading to a change in how we understand and describe the condition.

What does the term ‘Impingement’ mean?

Impingement means ‘to strike against’.

The Classic Impingement Model (Neer, 1970s) proposed that pain was due to bony compression of rotator cuff tendons beneath the acromion.

Impact: This led to surgeries such as subacromial decompression, though evidence shows little benefit.

Clinical Evidence Against the Impingement Model

Recent research shows that the age-old go-to treatment for shoulder pain, subacromial decompression surgery, offers no better results than a placebo, proving that ‘impingement’ may not really be the root cause after all.

Beard DJ (2018): Arthroscopic subacromial decompression is no more effective than placebo surgery.

Paavola et al. (2021): No superior benefit compared with placebo or structured exercise therapy.

Studies on the Acromio-Humeral Distance: Review of 15 studies showed that no difference between those with or without shoulder pain; not associated with pain/disability.

The End of the Impingement Era

Modern Understanding of shoulder pain proposes that the pain cannot be solely explained by a simple ‘pinching’ or ‘impingement’. Instead, the pathophysiology aligns more with tendinopathy, bursitis, and load-related tendon failure. Thus, a new term, Rotator cuff-related shoulder pain (RCRSP), is now used.

RCRSP is one of the most common causes of shoulder pain, with prevalence estimates ranging from 16% to 26% in the general population and higher among individuals performing repetitive overhead activities (e.g., athletes, manual workers).

Lewis, J. (2016): Emphasizes using ‘RCRSP’ instead of ‘subacromial impingement syndrome.’ Focus shifts to a patient-centred, functional approach rather than anatomical labels.

Glenohumeral Joint Biomechanics

Convex–Concave Rule — Does It Strictly Apply to the Shoulder?

A study by Donald A. Neumann states that when we look at shoulder biomechanics, it’s easy to assume that the humeral head simply spins in place, but in reality, it shifts in very specific directions depending on the movement.

For example, during external rotation, instead of sliding forward as many might think, the humeral head actually translates backwards across the glenoid, helping to preserve stability and joint congruency, which is also supported by Baeyens J-P (2000).

Massimini DF (2012) added that in abduction, rather than gliding downward, the humeral head moves upward toward the acromion, which explains why patients often feel a pinching sensation overhead when muscle control is lacking.

As proposed by Huegel (2015), in the early phases of elevation, the rotator cuff itself can come into contact with the subacromial arch, which is a part of normal motion but can turn painful if there is weakness or imbalance in the cuff or scapular muscles.

After about 70° of arm elevation, the rotator cuff no longer makes contact with the arch above. In fact, the acromiohumeral space is smallest at lower angles and then gradually opens up as you lift higher. So, in a healthy shoulder, the cuff isn’t actually being “impinged” all the way through the movement as stated by Giphart (2012).

Since modern evidence shows that true impingement does not occur, the condition is now described as Rotator Cuff–Related Shoulder Pain (RCRSP).

Okay, now let’s see how RCRSP often occurs. But before that, we need to take a deep dive into the rotator cuff.

Unveiling the Rotator Cuff—The Engine of Shoulder Stability

We all know the rotator cuff muscles—we’ve even studied the mnemonic SITS muscles:

- The supraspinatus is the primary abductor,

- Infraspinatus and Teres Minor are powering external rotation, and

- Subscapularis is driving internal rotation. Together, they work like a dynamic seatbelt, keeping your shoulder stable through every movement.

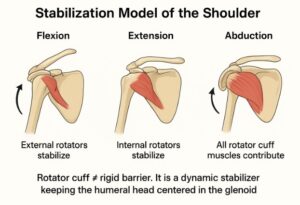

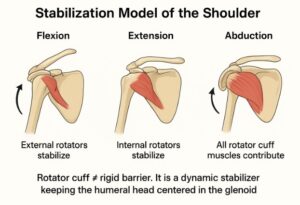

Stabilisation Model of the Shoulder

During Flexion, External rotators stabilise the shoulder.

During Extension, Internal rotators stabilise the shoulder.

During Abduction, all rotator cuff muscles contribute to stability.

Rotator Cuff Muscle Recruitment Patterns

Think of the rotator cuff as the “seatbelt system” of the shoulder. Its job is to stop the humeral head (ball) from sliding off the glenoid (socket) whenever you move your arm.

Now, here’s the interesting part: different cuff muscles work harder depending on the direction of movement.

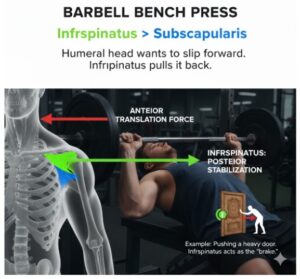

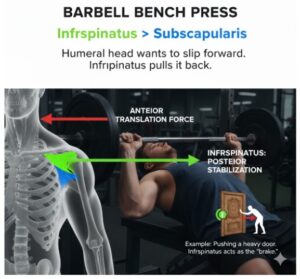

1. Bench Press (like Flexion – pushing forward)

- Infraspinatus works harder than subscapularis.

- Why? Because when you push forward, the humeral head wants to slip forward (anterior translation). The infraspinatus pulls it back to stop that.

Example: Imagine pushing a heavy door. As you push, the infraspinatus is like the “brake” stopping your shoulder from popping forward.

2. Row (like Extension – pulling backward)

- Subscapularis works harder than infraspinatus.

- Why? Because when you pull back, the humeral head wants to slide backward (posterior translation). The subscapularis resists that.

Example: Think of rowing a boat. When you pull the oar, your subscapularis tightens up like a safety strap to stop the ball from slipping backward.

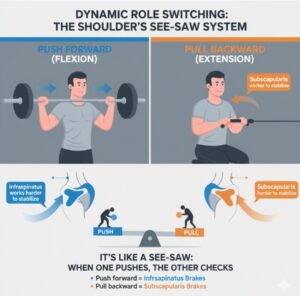

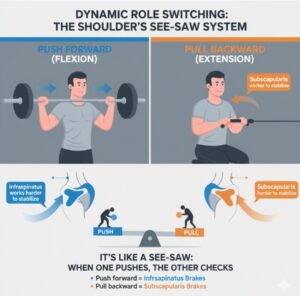

Dynamic Role Switching – See-Saw System

It’s like a see-saw: when one pushes, the other checks.

- Push forward (flexion-like movements) → Infraspinatus is the main stabiliser.

- Pull backwards (extension-like movements) → Subscapularis is the main stabiliser.

Adapted from the article on Rotator Cuff Recruitment Patterns by Wattanaprakornkul et al. (2011).

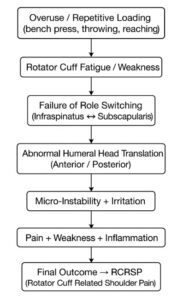

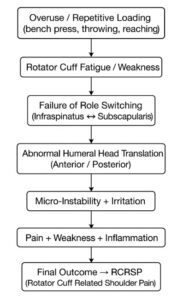

Mechanisms of RCRSP

Small Ache, Big Drama

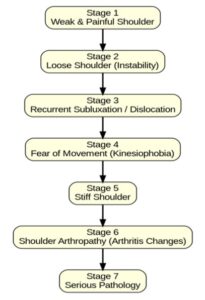

RCRSP can form a base for a wide range of shoulder pathologies. It starts as a weak, painful shoulder, innocent enough, until it decides to invite its friends: dislocation, stiffness, and degeneration.

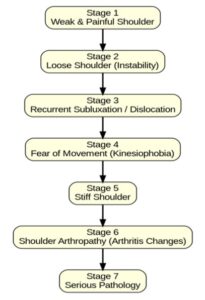

The Downhill Journey of a Shoulder: From Ache to Arthropathy

Stage 1 – Weak & Painful Shoulder: It all starts with muscle weakness and nagging pain, especially when reaching overhead.

Stage 2 – Loose Shoulder (Instability): The shoulder begins to feel wobbly, like it might slip out of place at any moment.

Stage 3 – Recurrent Subluxation/Dislocation: Small movements or minor force can now cause partial slips (subluxations) or full dislocations.

Stage 4 – Fear of Movement (Kinesiophobia): After repeated painful episodes, people start avoiding movement altogether—leading to restricted use of the arm.

Stage 5 – Stiff Shoulder: With less use and more guarding, the joint stiffens up, sometimes resembling a frozen shoulder.

Stage 6 – Shoulder Arthropathy: Years of instability and stiffness finally wear down the joint, causing arthritis-like changes.

Stage 7 – Serious Pathology: Advanced damage sets in, often leaving surgery (like joint replacement or complex repair) as the only option.

Diagnosis:

Diagnosing RCRSP involves a clinical approach. Since shoulder pain often presents with overlapping features, and imaging findings do not always correlate with symptoms, diagnosis is primarily based on clinical reasoning, functional assessment, and exclusion of serious pathology.

History taking:

History taking serves as a superior component in the assessment. Listening to the patient’s issue will be very helpful in identifying the pain patterns, activity-related pain, onset pattern, and aggravating/relieving factors. This leads to narrowing down toward a potential diagnosis.

Special tests:

Special tests are not always so special

Limitations of Traditional Special Tests

For decades, clinicians have relied on shoulder special tests such as Neer’s, Hawkins-Kennedy, Empty Can, and Drop Arm to diagnose rotator cuff problems. However, research has shown that many of these tests lack strong diagnostic value. In fact, Hughes et al. (2008) highlighted that most of these traditional tests have poor accuracy.

Updated Evidence from Meta-Analysis

More recent evidence paints a clearer picture. Zhao et al. (2024), in a large meta-analysis of over 3,000 patients, compared special tests against imaging and surgical gold standards.

The External Rotation Lag Sign emerged as the most reliable test, followed by the Internal Rotation Lag Sign. Moderate evidence was also seen for Jobe’s (Empty Can), Hawkins-Kennedy, and the Bear Hug Test. On the other hand, classic manoeuvres like Lift-Off, Patte, Drop Arm, and Neer’s offered little additional value.

- For Subacromial Bursitis / Impingement:

The Yergason’s Test, along with Neer’s, Hawkins-Kennedy, and the Painful Arc, showed moderate clinical usefulness. Interestingly, Jobe’s Test was not significant in this category.

Traditional tests are not entirely a waste, but they should not be used in isolation. Evidence now supports relying more on lag signs and a combination of special tests, interpreted within the clinical context, rather than depending on a single “classic” manoeuvre.

Think of special tests like puzzle pieces—use one alone and you’ll never see the whole picture.

Does imaging help all the time?

Imaging may help sometimes, but not all the time. An MRI can show you every millimetre of the rotator cuff—but guess what? It won’t tell you if the patient is losing sleep, avoiding overhead reach, or convinced their shoulder is “broken forever.” Scans capture anatomy, not beliefs, fears, or lived experience. That’s why shoulder care isn’t just about reading images—it’s about listening to people.

Imaging in Pain-Free People:

Pain ≠ Damage

Pain does not always equal damage—research shows that even people without shoulder pain can display abnormal imaging findings such as tears or degeneration.

Girish et al. (2011): 78% bursal thickening, 65% ACJ degeneration, 39% cuff tendinopathy.

Schwartzberg et al. (2016): 72% SLAP lesions in asymptomatic people

Guermazi et al. (2012): 68% cartilage defects, 72% bone osteophytes in asymptomatic people.

Practical Diagnostic Framework:

- History: Gradual onset, overhead pain, nocturnal pain, weakness.

- Exam: Use clusters of tests, not single ones.

- Imaging: Delay unless >12 weeks or surgery is considered. Ultrasound = cost-effective, compared to MRI.

- Reminder: Treat the Patient, Not the Scan

Managing RCRSP: From Ache to Action:

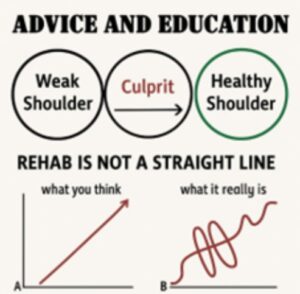

So how do we manage RCRSP before it grows from a small issue into a big culprit? Don’t let the small boy turn into a troublemaker.

1. Education First

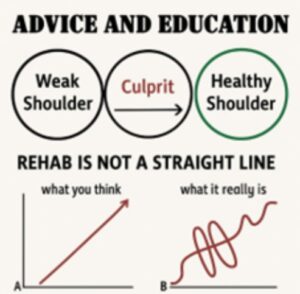

Patients need to know pain doesn’t always equal damage. Because their shoulder isn’t “broken forever.” Also, educate them that rehab is not a linear process.

Shoulder rehab isn’t a perfect upward climb—it’s more like an ECG wave. Some days you’ll feel stronger, other days you’ll dip. That’s normal, and progress still happens through those ups and downs.

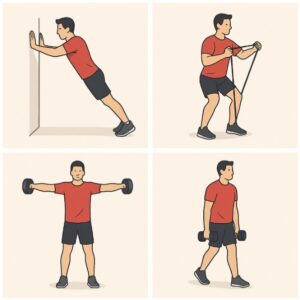

2. Exercise is Medicine

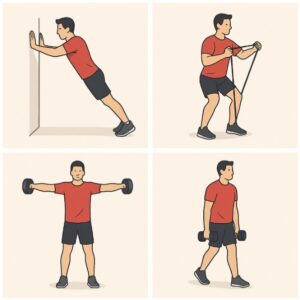

The best approach for shoulder problems is starting with exercise, especially motor control and progressive strengthening work hand in hand as the gold standard options, as suggested by Desmeules 2025.

Motor Control + Progressive Strengthening = Gold Standard

Guidelines recommend trying this conservative path as a first-line approach, and keeping surgery only for stubborn cases. Surgery is reserved for chronic, resistant cases.

In a 2024 Systematic Review & Meta-analysis by Lafrance et al., it is suggested that exercise therapy is the cornerstone, and motor control can really help your shoulder move and function better, but it may not completely take away the pain.

3. Functional Training

Remember: the shoulder is a worker, not a showpiece. So, encourage graded exposure; start light, build confidence, and let the shoulder remember it’s tougher than it thinks and include movements like,

- Push (horizontal & vertical)

- Pull (horizontal & vertical)

- Raise (yes, you’ll have to reach that top shelf again)

- Carry (because someone has to bring the groceries in)

4. Load Management

Shoulders hate two things: doing nothing, and doing everything at once. The sweet spot? Gradually increasing load without overwhelming the system.

Remind patients that recovery is more like a gradual strength program than a “quick fix.” Slow, steady loading wins.

5. Pharmacological & Injection Options:

- They should not be first-line.

- NSAIDs / Acetaminophen are appropriate for short-term symptom relief.

- Corticosteroid injections may provide short-term improvement, but effects diminish within months; no benefit for a longer period

Rehab Principles to Remember:

- Effective rehab doesn’t have to be complicated. The essentials are:

- Individualise it → Every patient is different.

- Keep it simple → Clear routines work best.

- Keep it going → Consistency beats intensity.

- Focus on problems, not pathology → Treat function, not scary labels.

- Movement over muscles → Train real-life patterns.

- Always have a plan → Patients need to know the “why” and “how.”

Simple, consistent, and patient-focused rehab wins every time.

Conclusion:

Understanding RCRSP means moving beyond the old “impingement” story. It’s not about a single structure being pinched, but about how the whole shoulder system, and the person behind it, responds to load, movement, and mindset. This shift reminds us that recovery is not just fixing tissue; it’s guiding people through the ups and downs of rehab with the right education, support, and plan.

So, the next time someone throws the word “impingement” at you, don’t panic—just smile, shake your head, and remind them: “There’s no such thing as shoulder impingement anymore.” Shoulder pain isn’t about something being pinched; it’s about a complex story of load, movement, and person. I hope that this blog clears the fog and gives you the confidence to answer back when someone says, “Your pain is because your cuff got impinged.” Now you know better, and knowing is the first step to healing.

Reference:

- Beard, David J et al. “Arthroscopic subacromial decompression for subacromial shoulder pain (CSAW): a multicentre, pragmatic, parallel group, placebo-controlled, three-group, randomised surgical trial.” Lancet (London, England) vol. 391,10118 (2018): 329-338.

- Lewis, Jeremy. “Rotator cuff related shoulder pain: assessment, management and uncertainties.” Manual therapy 23 (2016): 57-68.

- Lewis, Jeremy et al. “What’s in a Name? The Case for Using “Rotator Cuff-Related Shoulder Pain” in Clinical Practice.” The Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy vol. 55,7 (2025): 1-3. doi:10.2519/jospt.2025.13405

- Park, Soo Whan et al. “No relationship between the acromiohumeral distance and pain in adults with subacromial pain syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis.” Scientific Reports vol. 10,1 20611. 26 Nov. 2020, doi:10.1038/s41598-020-76704-z

- Neumann, Donald A. “The convex-concave rules of arthrokinematics: flawed or perhaps just misinterpreted?” The Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy vol. 42,2 (2012): 53-5. doi:10.2519/jospt.2012.0103

- Baeyens J-P et al. “Intra-articular kinematics of the normal glenohumeral joint in the late preparatory phase of throwing: Kaltenborn’s rule revisited.” Ergonomics vol. 43,10 (2000): 1726-37. doi:10.1080/001401300750004131

- Massimini, Daniel F et al. “In-vivo glenohumeral translation and ligament elongation during abduction and abduction with internal and external rotation.” Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research, vol. 7, 29. 28 Jun. 2012, doi:10.1186/1749-799X-7-29

- Huegel, Julianne et al. “Rotator cuff biology and biomechanics: a review of normal and pathological conditions.” Current rheumatology reports vol. 17,1 (2015): 476. doi:10.1007/s11926-014-0476-x

- Giphart, J Erik et al. “The effects of arm elevation on the 3-dimensional acromiohumeral distance: a biplane fluoroscopy study with normative data.” Journal of shoulder and elbow surgery vol. 21,11 (2012): 1593-600. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2011.11.023

- Wattanaprakornkul, Duangjai et al. “The rotator cuff muscles have a direction-specific recruitment pattern during shoulder flexion and extension exercises.” Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport vol. 14,5 (2011): 376-82. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2011.01.001

- Hughes, Phillip C et al. “Most clinical tests cannot accurately diagnose rotator cuff pathology: a systematic review.” The Australian journal of physiotherapy vol. 54,3 (2008): 159-70. Doi:10.1016/s0004-9514(08)70022-9

- Zhao, Q., Palani, P., Kassab, N.S. et al. Evidence-based approach to the shoulder examination for subacromial bursitis and rotator cuff tears: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 25, 1028 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-024-08144-z

- Girish, Gandikota et al. “Ultrasound of the shoulder: asymptomatic findings in men.” AJR. American journal of roentgenology vol. 197,4 (2011): W713-9. doi:10.2214/AJR.11.6971

- Schwartzberg, Randy et al. “High Prevalence of Superior Labral Tears Diagnosed by MRI in Middle-Aged Patients With Asymptomatic Shoulders.” Orthopaedic journal of sports medicine vol. 4,1 2325967115623212. 5 Jan. 2016, doi:10.1177/2325967115623212

- Guermazi, Ali et al. “Prevalence of abnormalities in knees detected by MRI in adults without knee osteoarthritis: population-based observational study (Framingham Osteoarthritis Study).” BMJ (Clinical research ed.) vol. 345 e5339. 29 Aug. 2012, doi:10.1136/bmj.e5339

- Diercks, Ron et al. “Guideline for diagnosis and treatment of subacromial pain syndrome: a multidisciplinary review by the Dutch Orthopaedic Association.” Acta orthopaedica vol. 85,3 (2014): 314-22. Doi:10.3109/17453674.2014.920991

- Lafrance, Simon et al. “The Efficacy of Exercise Therapy for Rotator Cuff-Related Shoulder Pain According to the FITT Principle: A Systematic Review With Meta-analyses.” The Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy vol. 54,8 (2024): 499-512. Doi:10.2519/jospt 2024.12453

- Desmeules, François, et al. “Rotator Cuff Tendinopathy Diagnosis, Nonsurgical Medical Care, and Rehabilitation: A Clinical Practice Guideline.” journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy 55.4 (2025): 235-274.