Why Do These Rules Matter?

According to a systematic review, OARs have consistently demonstrated high sensitivity in ruling out ankle fractures, making them a reliable first-line screening tool. So, they are helpful for:

- Reducing unnecessary X-rays – Avoid over-testing and extra radiation when it’s not needed.

- Speeding up care – Faster decision-making helps patients get the right treatment sooner.

- Co-relating with clinical judgment – When combined with professional expertise, OAR ensures safer, smarter care.

Use of special tests: What You Need to Know

- Accuracy is limited – No single test consistently delivers accurate, reliable or valid results.

- Some tests are useful but never in isolation – A 2022 systematic review by Smith J, et al. shows that Anterior drawer, anterolateral palpation, and reverse anterolateral drawer have either good sensitivity or specificity, but aren’t definitive on their own.

- Clinical expertise is key – Tests should be interpreted alongside the patient’s history and symptoms to ensure a more accurate diagnosis and effective care. (2)

The Imaging

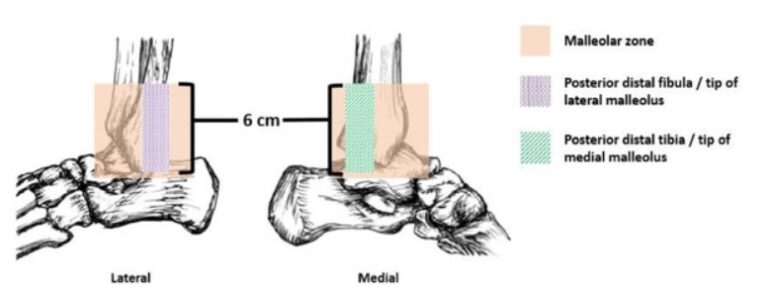

Know when to Image

- X-ray: Only when OAR is positive

- Ultrasound: Dynamic, cost-effective, and good for visualising ligament tears, joint effusion, or peroneal tendon pathology.

- MRI: Gold standard if symptoms persist beyond 4–6 weeks or when suspecting osteochondral lesions, syndesmotic injuries, or unexplained instability.

Start with clinical judgment and OAR. Escalate to imaging only when red flags or persistent dysfunction suggest “something more than a sprain”.

The Treatment

Does Ice Actually Help?

Clinician’s note: Ice has long been prescribed to reduce pain and swelling. But a 2021 systematic review found no clear benefit for pain, swelling, range of motion, or function compared with other treatments.

Athlete’s Takeaway: Ice may provide temporary relief from pain, but it doesn’t speed up healing or prevent further injury. Use it for comfort if needed, but focus more on structured rehab and movement rather than relying on cold therapy alone. (3)

What About Compression Bands?

Clinician’s note: Compression bandages have been widely used in the past, but current research does not support them as a standalone treatment for acute ankle sprains. While compression may offer subjective support, it does not improve clinical outcomes.

Athlete’s Takeaway: Compression wraps may provide a sense of support, but they won’t necessarily speed up your recovery. So, focus on active rehabilitation and movement instead. (4)

Should I Do Weight-Bearing or Not?

Clinician’s Note: Strong evidence supports early, supported weight-bearing even in Grade III injuries. Early weight bearing using aids like lace-up or semi-rigid braces encourages faster pain reduction, mobility, and swelling control compared to rigid immobilisation.

Athlete’s Takeaway: Start walking as soon as it feels safe, with support if needed. The sooner you move, the better your recovery. (5)

So, what can be done?

As per the Clinical Practice Guidelines 2021,

✅ Strongly Advised

– Early protected activity: Gradual return to function with the help of external support (semi-rigid braces, taping) if needed in the early phase, but it isn’t a long-term solution.

– Early supervised rehabilitation: Therapeutic exercises for strength, balance, and coordination speed recovery and reduce time away from sport. Careful monitoring ensures better outcomes.

– Tailored rehab program: Customised to the individual’s injury, goals, and recovery; progression guided by symptoms

➖ Can Be Considered

– Manual therapy & joint mobilisation: Offers short-term relief when combined with exercises, but shouldn’t be used alone.

❌ Not Necessary

– Electrotherapy, diathermy, ultrasound: Limited and inconsistent evidence; should only be used as adjuncts, not as core treatments.

– Long-term immobilisation: Rarely needed except in severe injuries or fractures; delays functional recovery. (6)

When do I have to consider surgery?

Surgery is considered when severe ankle instability or failed conservative rehab prevents patients from returning to their desired activities. It’s most commonly recommended for chronic lateral ankle instability (CLAI), where repeated sprains lead to persistent instability, reduced performance, and impaired function. As indicated in a systematic review, surgery offers excellent outcomes, with most athletes returning to sport within a few months, but factors like age and BMI must be considered, and recovery should also address psychological readiness and sport-specific rehab for the best long-term results. (7)

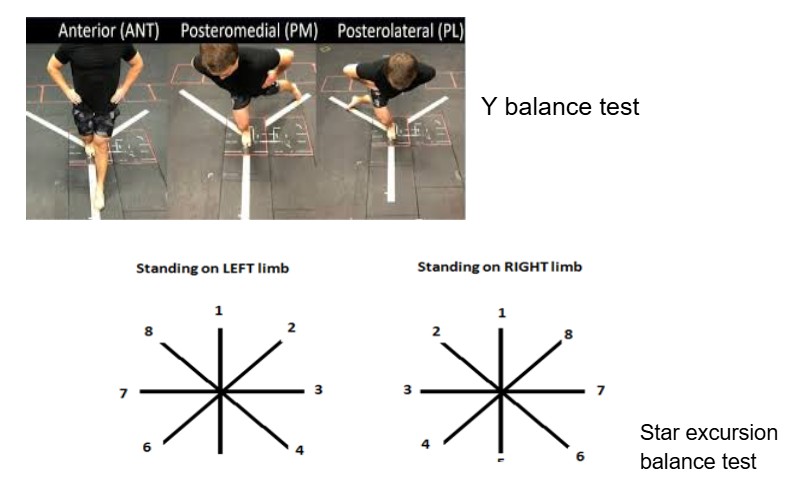

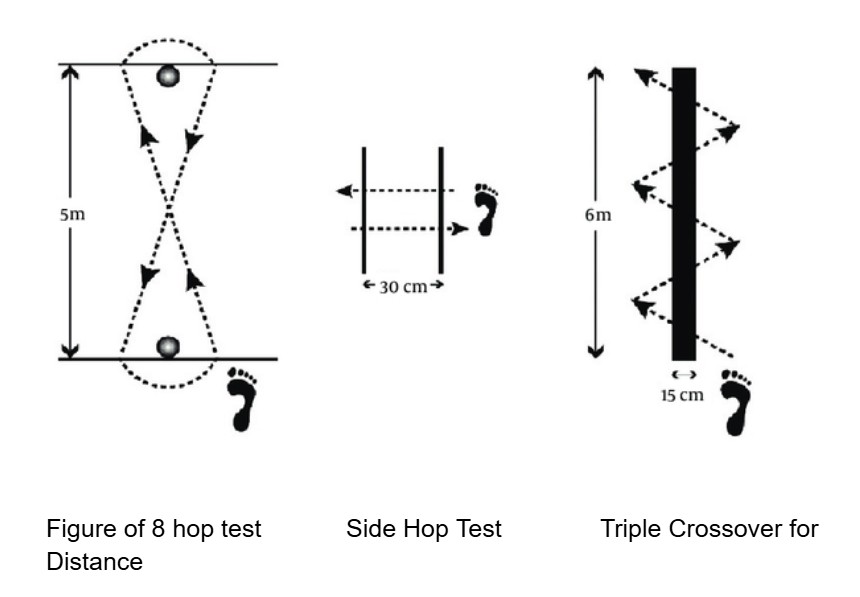

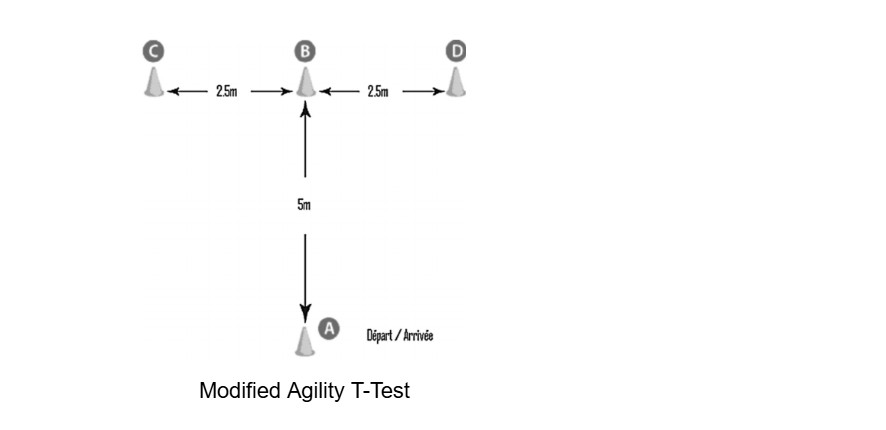

The Return To Sports

Returning to sport after an ankle sprain is often the biggest milestone for athletes, and is also the stage with the highest risk of re-injury if not handled carefully. Current evidence-based approaches ensure that athletes don’t just return quickly, but return safely, with reduced risk of setbacks and stronger long-term performance.

PAASS framework:

The PAASS framework provides a structured, evidence-based approach for guiding return-to-sport decisions following an acute lateral ankle sprain developed through an international multidisciplinary consensus using the Delphi method. (8)