Supine Roll Test (for horizontal canal BPPV)

- The patient lies flat while the head is quickly rotated left and right.

- A positive result is horizontal nystagmus when the head is turned to one side.

- If positive, this is highly suggestive of horizontal canal BPPV

Orthostatic Hypotension Test

Measure BP & HR lying, sitting, standing. A drop in systolic ≥20 mmHg or symptomatic dizziness suggests orthostatic hypotension, not inner ear disease.

“The questionnaire acts like a lighthouse, guiding us toward the broad category, and the tests help us decide in which direction to sail.”

Treatment

FOR BPPV:

Canalith Repositioning Procedure or Epley manoeuvre

- Canalith Repositioning Procedure (CRP), also called the Epley manoeuvre, for posterior canal BPPV, uses gravity to move loose inner ear crystals back to a safe spot, stopping vertigo.

- It is 4–10 times more effective than sham or Brandt-Daroff exercises, with 80–90% of patients improving after just one or two sessions. Anti-nausea medicine may be given if symptoms are severe during the procedure.

Procedure:

- Sit, head 45° to the affected ear.

- Lie back, head 20–30° down, wait.

- Turn your head 90° opposite side, wait.

- Roll to the same side, nose down toward the floor, wait.

- Sit up slowly, head slightly down

Semont Manoeuvre:

In a randomised control trial of 195 patients with posterior canal BPPV, both Epley and Semont-plus were safe and effective, but Semont-plus gave faster recovery (2 vs 3.3 days). Mild nausea was the only side effect.

Procedure:

- Sit, head 45° away from the affected ear.

- Drop quickly to the affected side, face up, and wait.

- Move rapidly to the opposite side, face down, wait.

- Sit up slowly.

For Non-BPPV (Vestibular Neuritis and Meniere’s)

A systematic review suggests that for vestibular neuronitis, doing rehabilitation exercises together with anti-vertigo drugs helps them recover faster and better than using either one alone, as recommended by the research evidence.

Medications: Steroids (reduce inflammation), antihistamines/betahistine (control vertigo), Vitamin B12 & sodium bicarbonate (nerve support).

Rehab: Vestibular exercises (habituation, adaptation, substitution, reconditioning).

Central vertigo is not treated with a single drug; instead, management focuses on treating the underlying cause and providing disease-specific treatment.

Other treatment approaches:

Tele-rehabilitation:

Doing vestibular rehab online (through video calls, apps, or remote monitoring) can reduce dizziness, disability, and anxiety. The results were similar to traditional in-person rehab, as shown by a 2024 Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis.

Patient education for vertigo, Lifestyle change, and Prevention

- Be cautious with head movements during mild dizziness.

- Manage underlying conditions like migraines or blood pressure.

- Maintain good hydration and a Low salt diet, especially in Meniere’s.

Vitamin D supplement:

A study done by Chua, Kenneth W De et al. shows that Vitamin D supplementation reduces BPPV recurrence in older adults with low vitamin D and may lower dizziness and fall risk.

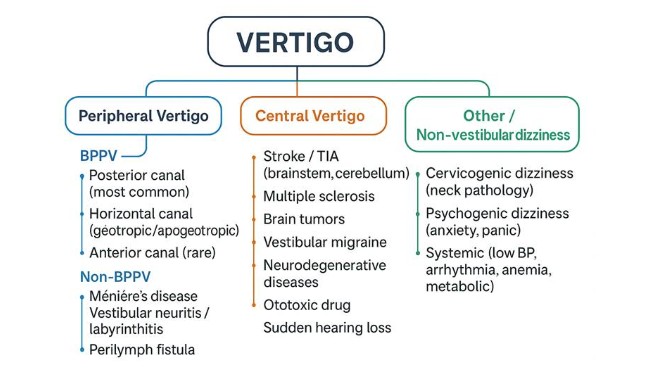

In this blog, I’ll go through a case of BPPV, a type of peripheral vertigo, showing how to differentiate it, confirm the diagnosis, and rule out other causes.

The charts above are just guidelines to help cut through the noise and narrow down the possibilities. Now, let’s put the guideline chart to the test and see how it works in practice.

Case study:

A 31-year-old female presented with a history of dizziness after her labour.

She states that she can’t lie on her back or bend forward, or move her neck freely, which seems to aggravate her dizziness, and the dizziness seems to extend for several seconds. In addition to that, she stated that she felt the room was spinning whenever she got up from lying to an upright position.

If we decode the history using a guideline questionnaire, we can clearly point towards “BPPV”

- Onset: Not sudden and continuous- rules out stroke / vestibular neuritis.

- Duration: several seconds- BPPV.

- Triggers: head movement/position change (lying, bending, neck movements, getting up)- classic BPPV.

- Hearing Symptoms: No hearing loss/tinnitus- rules out Meniere’s, labyrinthitis, fistula; Supports BPPV.

- Associated Symptoms: No neuro signs, no migraine features, no fainting- again supports peripheral cause (BPPV).

- History: Post-labour (stressful physiological event, but not trauma/infection). It could be linked with fatigue, positional habit, or even calcium/vitamin D shifts post-pregnancy, which increases BPPV risk.

What we understood from the questionnaire:

Her history checks almost every pivot for posterior canal BPPV:

Episodic, seconds of dizziness, triggered by lying down, bending, and standing up, spinning sensation (vertigo), no hearing or neuro symptoms.

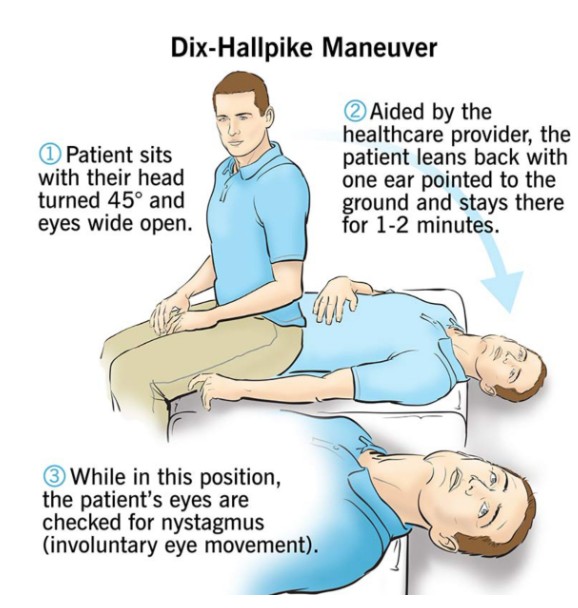

The next step is to do a test, but the problem is that if we assume she has BPPV and perform the test, it could give a false positive. So the better approach is to check for other possible causes first, rule them out, and then work back to confirm BPPV.

In this case, Dix-Hallpike was positive: BPPV (Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo)

Conclusion:

Vertigo isn’t the villain; our lazy diagnosis is. Every spin has a story, and unless you know the pivot point, you’re just guessing in the dark. So stop calling everything vertigo, start asking the right questions, and maybe next time you’ll actually treat the patient, not just the symptom.

Reference Article

- Bhattacharyya, Neil et al. “Clinical Practice Guideline: Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (Update).” Otolaryngology–head and neck surgery: official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery vol. 156,3_suppl (2017): S1-S47. doi:10.1177/0194599816689667

- Argaet, E C et al. “Benign positional vertigo, its diagnosis, treatment and mimics.” Clinical neurophysiology practice vol. 4 97-111. 6 Apr. 2019, doi:10.1016/j.cnp.2019.03.001

- Yetiser, Sertac. “Review of the pathology underlying benign paroxysmal positional vertigo.” Journal of International Medical Research 48.4 (2020): 0300060519892370.

- Strupp, Michael, et al. “Vestibular disorders: diagnosis, new classification and treatment.” Deutsches Ärzteblatt International 117.17 (2020): 300.

- Ohle, Robert, et al. “Can emergency physicians accurately rule out a central cause of vertigo using the HINTS examination? A systematic review and meta‐analysis.” Academic Emergency Medicine 27.9 (2020): 887-896.

- Burak, Kundakci, et al. “The effectiveness of exercise-based vestibular rehabilitation in adult patients with chronic dizziness: A systematic review.” F1000Research 7 (2018).

- Grillo, Davide, et al. “Effectiveness of telerehabilitation in dizziness: a systematic review with meta-analysis.” Sensors 24.10 (2024): 3028.

- Strupp, Michael, et al. “The Semont-plus manoeuvre or the Epley manoeuvre in posterior canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: a randomised clinical study.” JAMA Neurology 80.8 (2023): 798-804.

- Chua, Kenneth W De et al. “Randomised Controlled Trial Assessing Vitamin D’s Role in Reducing BPPV Recurrence in Older Adults.” Otolaryngology–head and neck surgery: official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery vol. 172,1 (2025): 127-136. doi:10.1002/oohn 54

- Chen, Jia, et al. “Effects of vestibular rehabilitation training combined with anti-vertigo drugs on vertigo and balance function in patients with vestibular neuronitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis.” Frontiers in Neurology 14 (2023): 1278307.