Introduction: More Than Just Back Pain

Almost everyone has experienced back pain at some point in life. But when that pain travels down the leg, burning, throbbing, or stabbing as if electricity is running through the nerves – it’s more than just a “backache.”

That’s lumbar radiculopathy. It happens when a nerve root in the lower spine gets compressed or irritated. This irritation can cause pain, tingling, numbness, or weakness that extends all the way down to the foot and toes.

Prevalence (how common it is):

- Low back pain affects 9.9–25% of people each year.

- The lifetime prevalence of back pain can be as high as 43%.

- Lumbar radiculopathy is among the most common neuropathic pain syndromes.

Why are L4–L5 & L5–S1 Discs prone to bulge?

Not all intervertebral discs are created equal. Some have important functions than others, and that makes them more vulnerable.

- High Mobility + High Load = Wear & Tear

The L4–L5 and L5–S1 discs allow a lot of bending, twisting, and rotation, but they also carry the heaviest loads of body weight. This combination makes them prone to bulging or herniation.

- Neck’s Weak Spots

Similarly, in the cervical spine, C5–C7 discs are frequent troublemakers. They give us a wide range of neck movements. But this increased mobility comes at the cost of stability, leading to increased mechanical stress on these segments.

Causes Of Lumbar Radiculopathy:

The lumbar nerve roots can get irritated or compressed by several conditions:

- Disc bulge or herniation (most common)

- Hypertrophy (thickening of facet joints or ligaments)

- Spondylolisthesis (a slipped vertebra)

- In rare cases: Tumours or infections pressing on nerves [1,8]

Think of the nerve root like an electric cable – any compression reduces the signal, leading to pain, weakness, or numbness.

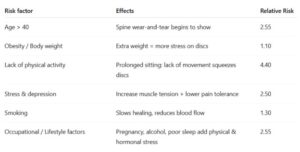

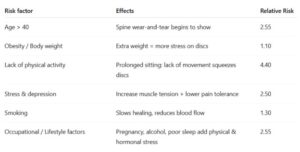

Risk Factors With Odds Ratio :

Not everyone develops radiculopathy, but some factors increase your odds of getting it.

Bottom line: Lifestyle plays a huge role in whether a small disc bulge stays silent or turns into painful radiculopathy.

Neurobiology Basis:

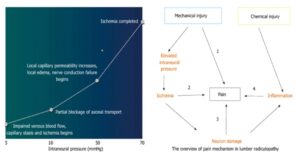

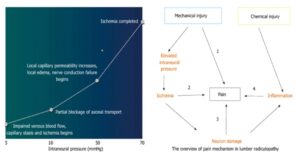

Mechanical injury and ischemia:

A herniated disc or spinal stenosis causes mechanical compression on the nerve root or Dorsal root ganglion (DRG). Compared to nerve roots, the DRG has a thin, permeable perineurium and has a dense blood supply. This makes it susceptible to damage and reduced blood flow (ischemia) when compressed.

Tissue Acidosis:

Mechanical compression causes a reduction in blood flow, resulting in venous congestion→intraneural pressure→ischemia →edema→reduced nerve conduction→reduced thresholds. Thus, more pain.

The lack of oxygen from ischemia forces the tissue to produce energy without oxygen. This process creates lactic acid, which lowers the tissue’s pH, leading to tissue acidosis.

Activation of Pain Channels:

The acidic environment activates two key pain-sensing channels on the nerve cells in the DRG:

- ASIC3: These channels are directly activated by the acid, allowing sodium to rush in and trigger a pain signal.

- P2X3: These receptors respond to ATP, a stored energy source released by damaged cells. They also help send pain signals.

The Result:

The activation of these channels and receptors results in the generation of pain signals, explaining how mechanical compression leads to the painful symptoms of lumbar radiculopathy.

Microgliosis in the Spinal Dorsal Horn:

Injury and Microglial Activation

A peripheral nerve injury triggers microglia (immune cells in the spinal cord) to become active. They increase in number and release inflammatory chemicals.

Neuronal Sensitization

These inflammatory chemicals, like cytokines, make nearby spinal neurons highly sensitive to pain. This means a non-painful stimulus can now be perceived as painful.

Neuropathic Pain

This neuronal sensitisation leads to neuropathic pain, a chronic condition. While microglia initiate this process, they often return to normal even if the pain persists, suggesting they are the “spark” rather than the “fuel” for ongoing pain. [1]

How Does It Feel? (Signs & Symptoms)

Patients usually describe lumbar radiculopathy as:

- Pain: Sharp, dull, piercing, burning, or throbbing.

- Worse with: Sitting, bending forward, coughing, sneezing.

- Better with: Lying down or walking (sometimes).

- Tingling/Numbness: Along specific “dermatomes” of the leg. The S1 dermatome seems the most reliable.

- Weakness: Foot drop (toe dragging), knee buckling, difficulty rising from a chair.

Doctors often separate symptoms into:

- Positive symptoms = Pain & tingling (overactive nerves).

- Negative symptoms = Weakness & numbness (underactive nerves- axonal loss, conduction block). [1,8]

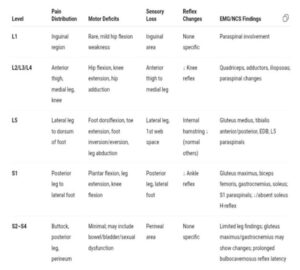

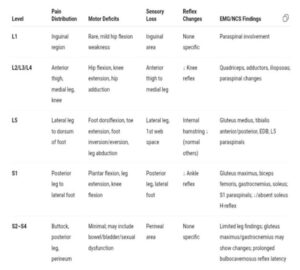

Clinical Presentation:

- The clinical presentations of lumbosacral radiculopathy vary according to the level of nerve root or roots involved. The most frequent are the L5 and S1 radiculopathies.[8]

How To Diagnose

History Taking:

Pain & Sensory Clues

- Tingling/Paraesthesia: 63–72%

- Radiating pain: 35%

- Numbness: 27%

Symptoms follow a specific lumbosacral dermatome

Motor Clues

Weakness in a specific myotome supports radiculopathy.

- Trouble rising from chair → Iliopsoas/Quadriceps weakness

- Knee buckling → Quadriceps weakness

- Toe dragging → Tibialis anterior weakness

Aggravating Factors

- Worsens with Valsalva / better lying down → Compressive cause

- Worsens lying down → Inflammatory / Neoplastic

- Onset often after bending, lifting, slipping, or trauma (30–50%)

Clinical Manoeuvres: Stress Tests for the Nerves

Straight Leg Raise (SLR):

Patient supine, symptomatic leg raised with foot dorsiflexed, which increases dural tension at low lumbar/high sacral levels.

Lasègue’s sign: Radicular pain (not back/hamstring) between 30–60° hip flexion.

Bowstring sign-Pain relieved with knee flexion

SLR is sensitive, esp. for L5/S1, but less specific

Contralateral SLR (Crossed SLR):

Raise the unaffected leg → pain in the affected leg.

Specific, but not sensitive, for disc herniation.

Reverse SLR (Femoral Stretch):

Patient prone, hip extended.

Evaluates L2–L4, but limited data on accuracy.

Patrick’s Test (FABER):

Hip externally rotated, knee flexed and placed on opposite leg.

Pain in the hip or buttock → suggests a hip/SI joint issue.

Not specific to radiculopathy. [8,5]

Neuroimaging:

- MRI, CT, and CT myelography are equally sensitive for diagnosing disc herniation.

- Abnormal MRI findings are common in asymptomatic people (e.g., disc herniation in 27% of asymptomatic subjects).

- MRI findings do not predict future low back pain development or duration.

Electrodiagnosis:

- NCS (nerve conduction studies) and EMG (electromyography) assess nerve root integrity and muscle innervation.

- Used when clinical symptoms persist but imaging is inconclusive, especially with neuromuscular weakness.[8]

Scoring tool for sciatica :

Differential Diagnosis:

Other causes/differentials:

- Lumbar spinal stenosis

- Cauda equina syndrome

- Diabetic amyotrophy

- Lumbosacral plexopathy

- Mononeuropathies of the leg (e.g., femoral, sciatic, peroneal, tibial nerve lesions.

Spinal Stenosis:

- Most commonly due to degenerative spondylosis

- Manifests as neurogenic claudication

- Bilateral/asymmetric leg pain, sensory loss, weakness

- Worsens with standing or walking

- Positive shopping cart sign

Cauda Equina Syndrome:

- Lesion caudal to the conus injures, in ≥2 of the 18 cauda equina nerve roots

- Symptoms: Bilateral leg weakness (L3–S1), Perineal sensory symptoms, Bowel, bladder, sexual dysfunction (S2–S4 involvement)

Diabetic Amyotrophy:

- Affects L2–L4 roots initially

- Uncontrolled diabetes for more than 12 years

- Symptoms: Proximal leg weakness, Pain, Dysesthesia

Other Important Considerations:

- Fever + back pain → suspect spinal infection (discitis, epidural abscess)

- Progressive weakness/gait issues/bowel-bladder dysfunction → suspect spinal cord or cauda equina compression

- Referred pain from retroperitoneum → suspect if: History of malignancy, Weight loss, Pain at night, Pain unrelieved by position. [8,5]

Radicular Syndrome :

Combination of radicular pain, Radiculopathy, and sciatica

TREATMENT Programme:

Lumbar Stabilization and Thoracic Mobilization

- Patients with chronic low back pain and radiculopathy showed a significant reduction in pain (VAS for low back and leg pain) and functional disability (ODI) after four and eight weeks of training.

- Improvements were observed with both open and closed kinetic chain exercise modes.

- Those who performed closed kinetic chain lumbar stabilisation and thoracic mobilisation achieved greater pain relief and better functional recovery than those who did only lumbar stabilisation exercises. [4]

Exercise Therapy

- Exercise therapy effectively reduces pain and improves function in lumbar disc herniation and radiculopathy.

- Improvements were evident through decreased VAS and ODI scores.

- No adverse events were reported across randomised controlled trials, supporting its safety and effectiveness as a core treatment approach. [9]

Psychological Aspects

- Chronic radiculopathy often leads to psychological distress, including fear, dependency, and emotional exhaustion.

- Prolonged symptom duration is associated with increased emotional burden and poorer coping mechanisms.

- These psychological factors negatively affect quality of life and interpersonal relationships, highlighting the need for a holistic, biopsychosocial approach.

Patient Education and Reassurance

- Education about pain mechanisms helps patients understand their condition and reduces anxiety and fear.

- Providing reassurance and realistic expectations mitigates maladaptive behaviours and promotes recovery.

- Physiotherapists play a crucial role in empowering patients, encouraging self-management, and enhancing treatment adherence through effective communication. [2]

Home-Based and Digital Exercise Programs

- QR code–based home exercise programs, combined with neurodynamic mobilisation and motor control exercises, enable structured, independent practice.

- These programs showed higher methodological quality and stronger evidence compared to conventional interventions.

- Digital delivery methods improve engagement, accessibility, and adherence to rehabilitation. [7]

Mulligan Techniques

- The Mulligan concept addresses lumbar disc dysfunction and sciatica.

- Commonly used techniques include:

- Spinal Mobilisation with Leg Movement (SMWLM)

- Bent Leg Raise (BLR)

- Traction Straight Leg Raise (TSLR)

- SMWLM produced the most significant improvements in pain, mobility, and function.

- Evidence remains limited due to the small number of studies and moderate methodological quality. [3]

Neural Mobilisation

- Neural mobilisation effectively decreases pain in both chronic and non-chronic radiculopathy.

- Greater disability reduction was seen in chronic cases with longer treatment duration and more frequent sessions.

- It supports pain relief, nerve mobility, and functional recovery when incorporated consistently in rehabilitation. [6]

References:

- Lin, Jiann-Her. “Lumbar radiculopathy and its neurobiological basis.” World Journal of Anesthesiology 3.2 (2014): 162.

- Samant, Pooja et al. “Understanding How Patients With Lumbar Radiculopathy Make Sense of and Cope With Their Symptoms.” Cureus vol. 16,3 e56987. 26 Mar. 2024, doi:10.7759/cureus.56987

- Hussein, Hisham et al. “A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Effectiveness of Mulligan Mobilisation with Movement on Pain, Range of Motion, Function, and Flexibility in Patients with Sciatica.” NeuroRehabilitation vol. 56,2 (2025): 83-96

- Kostadinović, Stefan et al. “Efficacy of the lumbar stabilisation and thoracic mobilisation exercise program on pain intensity and functional disability reduction in chronic low back pain patients with lumbar radiculopathy: A randomised controlled trial.” Journal of Back and Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation, vol. 33,6 (2020): 897-907.

- Khorami, Ahmad Khoshal et al. “Recommendations for Diagnosis and Treatment of Lumbosacral Radicular Pain: A Systematic Review of Clinical Practice Guidelines.” Journal of Clinical Medicine vol. 10,11 2482. 3 Jun. 2021, doi:10.3390/jcm10112482

- Lin, Long-Huei et al. “Neural Mobilisation for Reducing Pain and Disability in Patients with Lumbar Radiculopathy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Life (Basel, Switzerland) vol. 13,12 2255. 26 Nov. 2023, doi:10.3390/life13122255

- Arslan, Serpil, and Özlem Ülger. “The effect of exercise in the treatment of lumbar disc herniation: a systematic review.” Acta neurologica Belgica, 10.1007/s13760-025-02767-2. 25 Mar. 2025, doi:10.1007/s13760-025-02767-2

- Philip S Hsu et al. “Acute lumbosacral radiculopathy: Etiology, clinical features, and diagnosis”

- Du, Shaojie et al. “Clinical efficacy of exercise therapy for lumbar disc herniation: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.” Frontiers in medicine vol. 12 1531637. 28 Mar. 2025, doi:10.3389/fmed.2025.1531637